By Order of the Pesky Timers

Reflecting on the Fish and Fugues in Carlo Rovelli's "The Order of Time"

“It is a strange thing, but when you are dreading something, and would give anything to slow down time, it has the disobliging habit of speeding up.” — JK Rowling, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire

Dear Reader,

The Order of Time was gifted to me by my dear friend and mentor, Sebastian, a German physician and a human encyclopedia bespectacled by Dumbledore-esque glasses. He knows just the right books that suit my interests, but he clearly overestimates my ability to comprehend quantum mechanics.

Written by Carlo Rovelli, an Italian theoretical physicist, head of the Quantum Gravity group at the Centre de Physique Théorique of Aix-Marseille University, and one of the founders of the Loop Quantum Gravity theory, The Order of Time is an Italian-to-English translation of science history, philosophy, and of course, theoretical and quantum physics centered around the concept of Time as experienced by humans on Earth. Rovelli writes in a very layman-friendly manner but that doesn’t alleviate the innate complexity of theoretical physics. Luckily, amid his explanations of quantum physics I found Rovelli’s incites on the familiar complexity of the human condition and our collective suffering of time.

“What causes us to suffer is not in the past or the future: it is here, now, in our memory, in our expectations. We long for timelessness, we endure the passing of time: we suffer time. Time is suffering.” — Carlo Rovelli

Rovelli starts off explaining humanity’s relationship with time by stating “we are in time as fish are in water.” I accept this analogy, but that’s a rather daunting thought, if you really think about it. The average fish that never surfaces probably does not know what water is. Water is just where they exist; they probably have no conscious awareness of it. If we really are in time as fish are in water, then we are not as consciously aware of time as we think we are. Here is a snippet of David Foster Wallace’s “This is Water” 2005 Kenyon College commencement speech as the case in point:

But, I guess humans are much more inquisitive about the world around them compared to fish. Since the dawn of man, humans realized that there was some sort of rhythm to their lives (it’s the diurnal or circadian ones, as it turns out), and so they quantified said rhythm. Rovelli shares that the word “time” is derived from an Indo-European root: di or dai — meaning to divide. Rotations around the sun were divided into months, days, hours, minutes, seconds, etc. The standardized measurements of time are universally accepted (and by universally, I mean on Earth). And with this standardized measurement of time using intricate and precise mechanisms in both analogue and digital clocks (or a nifty pocket-watch!), humans have successfully quantified time enough to organize their lives.

“As well as the days, we then count the years, and the seasons, the cycles of the moon, the swings of a pendulum, the number of times that an hourglass is turned. This is the way in which we traditionally conceived of time: counting the ways in which things change.’ —Carlo Rovelli

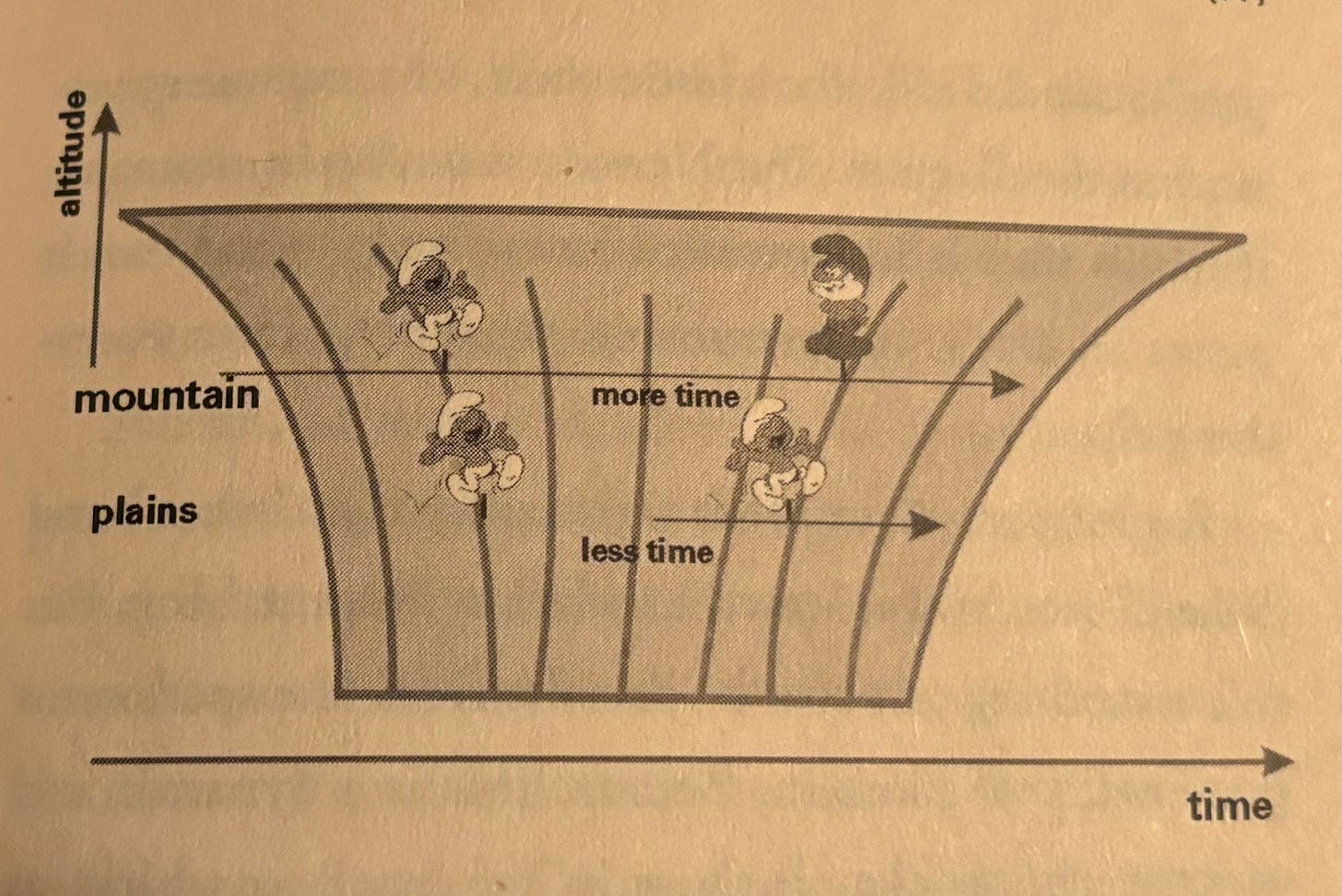

However, time is more than just notches on a clock or squares on a calendar. There is not one time (or rather, present) that befalls the universe. According to Rovelli, Newton was the first to suggest that time is part of the spatiotemporal fabric which is a gravitational field. The gravitational field is spacetime. This is a stretchy invisible (at least to us) fabric that contracts where the mass causing the gravitational pull sits, and expands away from the source of gravity. Because the spacetime fabric is tighter near gravity, it is said that less time exists there compared to further away from gravity (see illustration below).

Rovelli gives this example: if there is a set of twins, one living in the plains and one living in the mountains and they meet again after some time has passed, the one in the mountains would have aged more than the one living in the plains, albeit slightly. But here is where I’m puzzled: keeping with the analogy of us being in time like fish are in water, if more time exists away from the source of gravity, does it mean that people who exist there have experienced all of that time? In other words, if there is more water for the fish, does it mean that the fish have swam in it all? Maybe I’m asking the wrong questions because Rovelli states that there are precise clocks in physics labs that can capture these differences in passing time near and far from centers of gravity. I will unbend my mind eventually.

Another concept Rovelli shares is that in a world devoid of time, events wouldn’t stop or be “frozen in time”. In fact, all events would happen simultaneously in a chaotic fashion because time gives events their linear and orderly nature. This still bewilders me if we were to stay true to the fish-water idea. If we take water away from the fish, they plummet to the abyss of the oceans. They don’t swim anywhere. Without their water, nothing happens to the fish. In my mind, if we remove time, then we get nothing and probably end up in a place like this:

Ok, maybe I am thinking of this fish-water analogy as if it’s doctrine when Rovelli probably meant that we are inseparable from time because we are immersed in it. It is not easy to figure out exactly how it works because of the vantage point from which we are experiencing it. He provides the examples of the rotating constellations in the night sky or the rising and setting sun giving the illusion that we are stationary and they are in motion—that is until science proved otherwise. Similarly, we still don’t know where we are relative to time (but maybe we are immersed in it like fish in water?). Ultimately, Rovelli leaves us with the enigmatic but plausible claim that our perception of time is really internal.

Rovelli explains further that time is measurement of change and “the world is nothing but change.” He argues that the universe is not a collection of things but rather a collection of events. “The world is not so much made of stones as of fleeting sounds, or of waves moving through the sea.” (this is where Sebastian wrote in the margins of the book “The world is a fugue, Ola!). Any thing was something else at one point and will become something else later. Every thing is at a different stage of its becoming the next thing and its life cycle varies from other things. Hence, Sebastian’s fugue remark. Here is a visualization of one of the most famous fugues that somewhat resembles Rovelli’s (and Sebastian’s) point:

The book then takes a more complex turn that even Rovelli sympathized with readers and gave permission to skip ahead to less quantum mechanics-heavy chapters. But what caught my attention is, while this book is significantly different from Bittersweet by Susan Cain (which was reviewed in last week’s post Sweet Sorrow: Finding Inspiration in the Somber), there is a common denominator which is the acute awareness of passing time and longing for timelessness. Rovelli gave a less scientific and more human definition of time as he digressed with reflection about an old colleague at Princeton:

“This is time for us. Memory and nostalgia. The pain of absence. But it isn’t absence that causes sorrow. It is affection and love. Without affection, without love, such absences would cause us no pain. For this reason, even the pain caused by absence is, in the end, something good and even beautiful, because it feeds on that which gives meaning to life.”

With all this nostalgia and longing for the past in mind, how can one not get excited with anticipation that the secrets of time travel may be finally revealed in this book? But, alas.

While Rovelli does not explicitly share any particular hints as to how one may go back to the past, he does share an interesting concept about why time travels in one direction. Here is my attempt at putting it in my own words. Based on Rovelli’s thermal time hypothesis, the direction of time is determined by the second law of thermodynamics, which states that entropy always increases. Things start out in a state of low disorder and move to a state of higher disorder while generating heat in the process. That’s the general flow of the universe — onward and upward and into chaos from its singular origin since the Big Bang. The past is the past because the probabilities of how events unfold have been determined and the possible outcomes have been settled. The future is a higher state of entropy where the probabilities are plenty (relative to the past), and so the manner in which events will land in the future - the tip of the arrow of time - is yet undetermined. [Phew!]

And with that, the secret to time travel is obvious: reverse the laws of thermodynamics! (I guess…?) But until someone figures that out, if ever, we will continue to suffer time especially when we look in the rearview mirrors of our lives — photo albums, old letters (or emails), year books. These memory activators put time in perspective as we count up the years (and blessed are those who reach bigger numbers in their count). Luckily, our memories are the bittersweet gifts that allow us to transcend time.

As human beings, we live by emotions and thoughts. We exchange them when we are in the same place at the same time...we are nourished by this network of encounters and exchanges. But, in reality, we do not need to be in the same place and time to have such exchanges. Thoughts and emotions that create bonds of attachment between us have no difficulty in crossing seas and decades, sometimes even centuries, tied to thin sheets of paper or dancing between the microchips of a computer. We are part of a network that goes far beyond the few days of our lives and the few square meters that we tread. This book is also a part of that weave…” — Carlo Rovelli, The Order of Time

Have you read The Order of Time? What does Time look or feel like to you? Share your thoughts!

Till next time (ha!),

O